18 April 2018, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Population data suggests that Sri Lanka is one of the least urbanised countries on earth. Recent spatial analysis challenges this representation, suggesting rapid urban expansion in peripheral areas is not captured in population statistics.

18 April 2018, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Population data suggests that Sri Lanka is one of the least urbanised countries on earth. Recent spatial analysis challenges this representation, suggesting rapid urban expansion in peripheral areas is not captured in population statistics.

Sri Lanka’s urban expansion

UN-Habitat is currently assessing the spatial dynamics of Sri Lanka’s urbanisation. The analysis is being conducted across the country’s 9 provincial capitals for the period 1995-2017. The project is on-going, with results to be published later this year in the State of Sri Lankan Cities Report, but the data generated so far suggests that Sri Lanka’s cities have expanded rapidly since the 1990s.

Preliminary spatial analysis suggest that in the capital, Colombo, the urban built-up area increased from around 41 km2 in 1995 to 281 Km2 in 2017, while non-built up areas diminished from 125 Km2 to 10 Km2 (Fig 1). This trend of urban expansion is unprecedented in the city’s history, with a far greater urban area added in the years 1995-2017 than at any other time in the settlement’s existence.

Fig 1: Colombo urban expansion*

Source: UN-Habitat State of Sri Lankan Cities Report (forthcoming)

Source: UN-Habitat State of Sri Lankan Cities Report (forthcoming)

*Images show extent of area showing urban land use characteristics in UN-Habitat analysis.

Colombo’s rapid urban expansion is mirrored across the other provincial capitals. The preliminary results suggest that during the period 1995-2017, urban area grew by 9.57 per cent per year, which is a remarkably high figure even by global standards. A cross country review of over 300 spatial case studies reported far lower average annual rates of urban spatial growth in Europe, North America, Africa, India and China during a reference period of 1970-2000 (Fig 2).

Sources: Sri Lanka, UN-Habitat State of Sri Lankan Cities Report (forthcoming); Others, Seto et al. (2014)

Sources: Sri Lanka, UN-Habitat State of Sri Lankan Cities Report (forthcoming); Others, Seto et al. (2014)

* Sri Lanka reference period 1995-2017 for 9 provincial capitals; Others, 1970-2000

Sri Lanka’s exceptionally small urban population

While news of rapid spatial expansion will come as no surprise to those commuting through Colombo’s seemingly endless urban sprawl or visiting the bustling centres of Kandy and Galle, evidence of Sri Lanka’s booming cities are incongruous with its official position as one of the most rural societies on earth.

Sri Lanka ranks as the fifth least urbanised out of 233 countries, according to the UN’s 2014 World Urbanisation Prospects, with a marginally lower urban to rural population ratio than Niger, St. Lucia and South Sudan. Officially, only around 18 per cent of Sri Lankans live in an urban area – or around 3.9 million out of the country’s 21.2 million, according to World Bank data. This figure is far below the global average of around 50 per cent, and is the joint lowest in the South Asian region (Fig 3).

Source: UN World Urbanisation Prospects 2014

Source: UN World Urbanisation Prospects 2014

Perhaps more surprising, Sri Lanka’s urban rural population ratio registers a decline over the past 50 years, according to census data. This downward trend is without parallel in the South Asian region and, indeed, is rare globally.

Sri Lanka’s urban population dynamics are inconsistent with the country’s rapid economic development over the past decade, because globally studies have shown that economic growth is highly correlated to urbanisation.

In 2016, Sri Lanka’s per capita GDP was USD 3,910 – the third highest in South Asia, according to World Bank data. It was seven times higher than the per capita GDP of Afghanistan, and more than double those of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh – yet Sri Lanka’s urban population ratio is far lower than these South Asian neighbours. Nepal, which has an equal urban to rural population ratio, recorded a per capita GDP of just USD 729.

Defining ‘urban’ in Sri Lanka and why it matters

Sri Lanka’s small urban population and low rate of urbanisation is difficult to reconcile with the spatial and economic indicators of rapid urban growth. A key reason for these mixed messages is related to how ‘urban’ is defined in the Sri Lankan context.

What counts as ‘urban’ population data is directly related to administrative boundaries that demarcate rural and urban areas. Those that live within the government demarcated urban boundary are classed as urban residents, and those within rural boundaries are counted as rural residents.

This practice has led to errors of exclusion, where those in rapidly urbanising peri-urban spaces are not counted as urban.

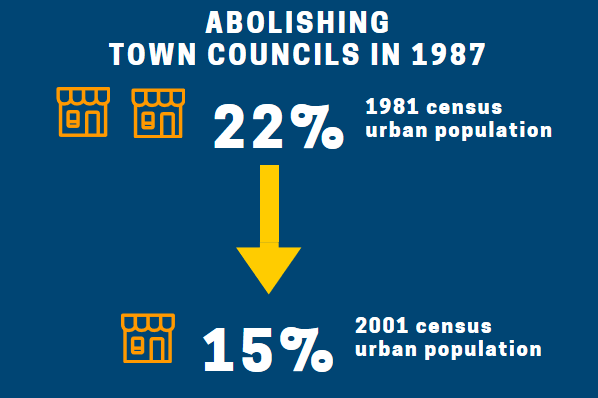

This administrative definition of urban also accounts for the country’s apparent trend of de-urbanisation. In 1987, the country changed its urban boundaries by abolishing the unit of ‘Town Councils’, resulting in an overnight reduction in its urban population. Since then, the boundaries have not been substantially changed and so the population defined administratively as urban has remained relatively static. In contrast, the land areas showing urban spatial characteristics have expanded rapidly.

The ambiguity over what counts as a city presents significant barriers to understanding urban systems and so constrains effective urban policy making.

To take an illustrative example, an assessment of Colombo’s flood risk based on an administrative or population-based definition of urban would give a skewed view of city-wide trends. This is because large swathes of areas in the periphery, which display urban characteristics but are administratively classed as rural, would not be included. Not accounting for these rapidly urbanising areas, where infrastructure deficits and flood risks are often distributed, could have severe implications for the sustainability of cities. It is also in the periphery where the range of challenges associated with fast-paced urban development are most apparent, including the environmental impact of uncontrolled urban sprawl in relation to destruction of wetlands, commuting and traffic congestion, and a range of other issues to be explored in the State of Sri Lankan Cities report.

It is crucial that policy makers arrive at a standard, accepted definition of ‘urban’ in Sri Lanka that includes these rapidly urbanising peripheral areas. Such a definition will provide a solid foundation for effective, holistic urban policy and planning.

The State of Sri Lankan Cities Project, funded by the Government of Australia, is implemented by UN-Habitat in close collaboration with the Government of Sri Lanka from 2017- 2018. Key project partners include the Sri Lanka Institute of Local Governance, Urban Development Authority, Local Authorities of the nine Provincial Capitals and the Asia Foundation.